The rise of Nairobi’s concrete tenement jungle

This important article was written by urban planner Baraka Mwau. In years to come this research will be recognised for its critical insights. This is the image of Africa’s future urban form for the majority of its city dwellers.

Early evening in the inner-city district of Pipeline-Embakasi in Nairobi, Kenya (Photo: Baraka Mwau)

On a hot and hazy Sunday afternoon, Nairobi’s concrete tenements loom over the city’s shacks (or ‘slums’). Men and women hang clothes on rooftops and balconies – making the buildings appear as a patchwork of fabric mosaics. The streets below buzz with activity: hawkers, stallholders, water vendors and pedestrians bustle among shops, betting joints, cafes and bars. People stream in and out of the tenement’s ground floor gates. Children play.

On the balconies, some tenants pass time in the only place where the building opens up to the air outside. This is something of a luxury – many tenants have inward-facing balconies or live on floors with only artificial lighting. Neither sunlight nor fresh air find their way through here.

Meanwhile, water starts to run again from the only tap on the floor (sometimes the only one in the building) and queues are building up. The building caretaker scales the floors letting tenants know the vital service is on again. Back outside, as the evening closes in, pedestrians pour to and from the matatu pick-up point. Matatu is Nairobi’s informal public transport, including buses, minibuses and vans.

These scenes of tenements and their surroundings are common in the inner-city areas of Pipeline-Embakasi, Kayole, Githurai, Baba Dogo, Mathare Valley and Huruma among others.

Blocks of seven and eight-storey tenements in Pipeline-Embakasi (Photo: Baraka Mwau)

Blocks of seven and eight-storey tenements in Pipeline-Embakasi (Photo: Baraka Mwau)

The transition from shacks to tenements

Research by SDI-Kenya under the East African Research Fund (EARF) has been analysing shelter options in Nairobi, focusing on provision to low-income groups. This research shows these groups mainly occupy rental single-room units.

In the past, shacks have dominated supply of the single-room unit. But the last three decades have seen tenements increasingly take over as the future of Nairobi’s ‘low-cost’ rental housing. Tenements are rental walk-up, high-rise structures averaging eight floors, but sometimes rising as high as ten. Multiple single-room units are densely packed into each floor.

The rise of the tenement submarket has essentially been a form of ‘slum upgrading’ driven by the private sector. There have been three main types of transition:

- In-situ spontaneous transition of individual shack structures to tenements

- Redevelopment of entire slum settlements or previously planned low-cost housing schemes (eg Kenya’s 1980s ‘site and service schemes’), and

- Greenfield tenement – in newly subdivided land,

So, what motivated the transition to tenements? In short, they rose out of Kenya’s structural adjustment reforms of the 1980s. Market liberalisation expanded room for the private sector in housing supply. At the same time, local government’s capacity for effective urban planning and management diminished, and remains ineffective – the city has huge backlogs of infrastructure and affordable housing.

Faced with a rapidly growing population alongside low incomes and rising unemployment, private capital emerged to provide ‘low-cost’ rental housing and this new submarket emerged.

For developers, tenements are a lucrative business. High demand brings a market ripe for the picking. Development requires relatively small capital injections and the returns are healthy: investment is often recouped within five years. Maintenance costs are low.

Multi-storey tenements are replacing shacks in many inner city areas of Nairobi (Photo: Baraka Mwau)

Multi-storey tenements are replacing shacks in many inner city areas of Nairobi (Photo: Baraka Mwau)

Behind the stone and mortar

Tenements provide much-needed affordable shelter for many of Nairobi’s residents. Monthly rent for a unit typically ranges from Ksh. 3000 (US$30) to 5,000 ($50). As well as shelter, the ground units provide commercial space for businesses. This creates a vibrant local economy that supports livelihoods for thousands of households and has made the streets more active.

But these concrete jungles present a critical urban governance challenge. They are mostly built without planning approval and so go against building regulations.

Indeed, the lack of regulation around tenements has seen buildings collapse with tragic consequences. And the development of tenements has created a melting pot of different actors including developers, contractors, land dealers, politicians, public officers, community leaders and local gangs among others.

Tenants often have perceptions that tenements – with their stone and mortar walled units – offer better shelter than shacks, are safer, more affordable and in some sense, more dignified. But do tenements provide better housing?

Tenements have essentially reproduced the inadequate single-room unit of shacks. They are densely occupied to maximise vertical space, and in turn are more overcrowded. They are poorly designed – lower floors lack ventilation and have little or no natural lighting. Water and sanitation provision are inadequate. They offer limited outside space and amenities such as schools or recreation areas.

Overcrowded, sub-standard housing has been linked to social and health problems, which may affect women and children disproportionately (PDF). The flights of stairs present major challenges for small children, the elderly, the sick and disabled.

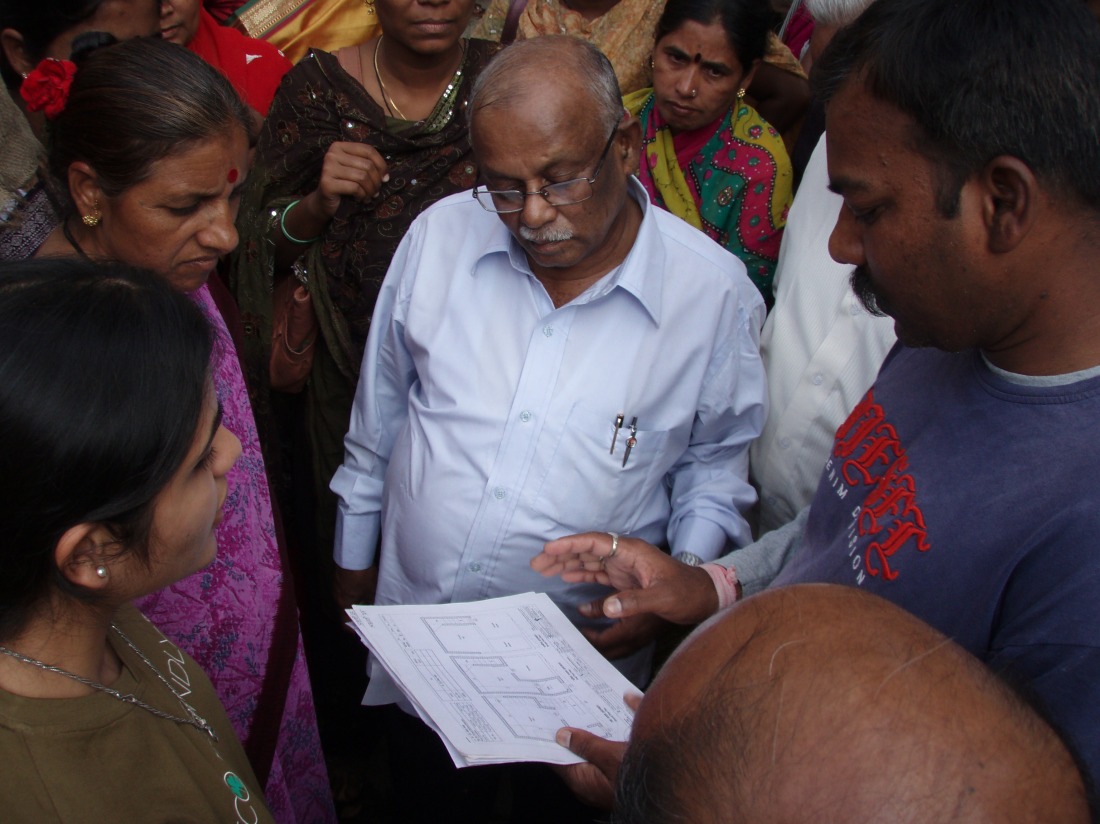

A plan showing the layout of a typical tenement (Image: Baraka Mwau and Sammy Muinde)

A plan showing the layout of a typical tenement (Image: Baraka Mwau and Sammy Muinde)

What does the future hold?

What are the policy, health and social implications of this expanding generation of tenement tenants? To date, research on Nairobi tenements is scant. Research on upgrading programmes largely focuses on shack housing; any emerging research on tenements tends to focus on the political economy of tenement production and the nature of housing from the planning and design perspectives.

As the EARF project highlights, more work is needed to understand the social, economic and health impacts of tenement living.

As well as the socio-economic impacts, further concerns arise from fraught tenant-landlord relations. Despite unregulated planning, tenement renting often carries formal ‘contract-like’ agreements. Powerful landlords pursue their interests, often at the expense of vulnerable tenants.

In the absence of foreseeable improvements, it is unclear how tenants will mobilise to demand improved housing conditions. Likewise, concerns arise on how policy interventions will fare after decades of piecemeal slum upgrading projects.

Policy and practice will need to revisit the root causes of what is shaping the transition to ‘low-cost’ housing in Nairobi. While the recent comeback of Kenya’s government in housing is commendable, the current focus on greenfield areas (developments built on new pieces of land) and redeveloping old estates (PDF) will need complementary programs for addressing living conditions in existing shacks and the rapidly expanding tenement areas.

Apologies for the long delay. Here is Chapter 11 – Uganda.

Apologies for the long delay. Here is Chapter 11 – Uganda.